September 2020 Issue Index

Uncertainty in domain modelling

Maptek DomainMCF generates models that include a measure of uncertainty, which can be used to make informed decisions and compliant resource statements.

To report a resource from a geological model requires three components – volume, density and grade or quality.

This model should portray the best understanding of geological processes and observations. However, a volumetric interpretation of geological observations is only as good as the knowledge, experience, biases and patience of the geoscientist building the model.

In reality, several possible interpretations could be generated by multiple geologists, and as such geological uncertainty is just as important as grade uncertainty.

This geological uncertainty often gets overlooked, primarily because unlike grade uncertainty, there is no easy way of capturing or communicating it.

Often, model revisions are generated only every three to six months. This limits the geologists’ ability to test geological hypotheses, or quickly embed new learnings globally and develop new models for short term implementation.

Using DomainMCF to predict geological domains is a highly efficient process, requiring little in the way of input parameters. This approach generates models that include a measure of uncertainty, which can then be used to make informed decisions.

Drilling budgets can be targeted at areas of high uncertainty, rather than drilling out on a grid basis in a zone of geological homogeneity. Drillholes can be designed to hit these targets using the new Drillhole Optimiser available in Vulcan 2020.

Lisheen case history

A case history using data from the Lisheen base metal mine in Ireland shows several possible interpretations for geological domain boundaries made from the same drilling data.

Just as three different geologists can interpret the data in three different ways, machine learning can emulate the same process but with several orders of magnitude in speed improvement.

All solutions honour the data, highlighting the underlying uncertainty that exists in most geological settings that have been interpreted from subsurface data such as drilling and downhole geophysics.

Each model generated for this case history took 10 minutes to complete using DomainMCF, compared with a week of effort by the mine geologist during the mine operation according to Colin Badenhorst, former Mine Geologist at Lisheen.

Uncertainty can also be used to better quantify confidence when assessing resources and reserves stated compliant to the JORC code, reducing the subjectivity around the process.

The models were used to quantify volumetric uncertainty for the geological domains generated from the widely spaced exploration drillholes.

The models of the main mineralised body exhibited a volumetric variation of 12% between the most optimistic prediction of the geological domains and the most pessimistic interpretations.

This is an important observation, as a variation of this magnitude will affect the resource statement.

Instead of a statement such as ‘1 million tonnes at a grade of x’, the more appropriate wording would be ‘1 million tonnes (+/- 6% or +/- 60,000 tonnes) at a grade of x’.

The alternative statement provides mine planners and potential investors with a quantitative assessment of the risk due to geological uncertainty.

Acknowledgements to

S. Sullivan, C. Green, D. Carter, H. Sanderson and J. Batchelor ‘Deep Learning: A New Paradigm for Orebody Modelling’, and

Colin Badenhorst, Mine Geologist at Lisheen, 2004-06

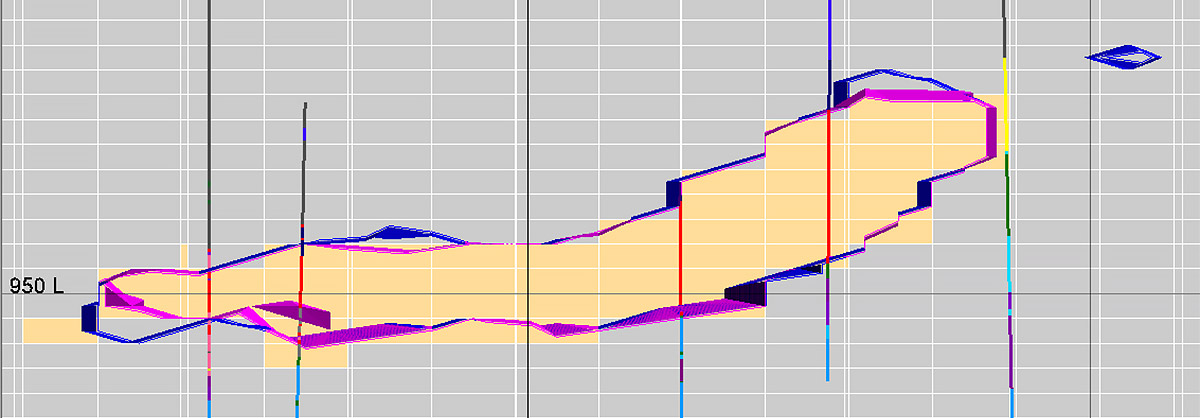

This cross-section through exploration drilling and wireframe outlines of two DomainMCF predictions of one of the Lisheen orebodies is shown against a background of a third DomainMCF domain prediction.

Subtle differences appear between the three models, each representative of the lithological drill logging.

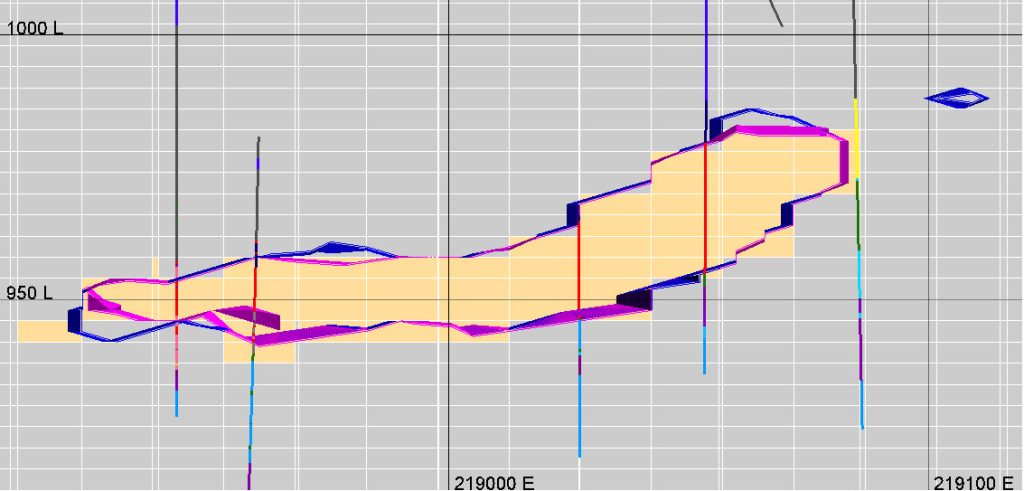

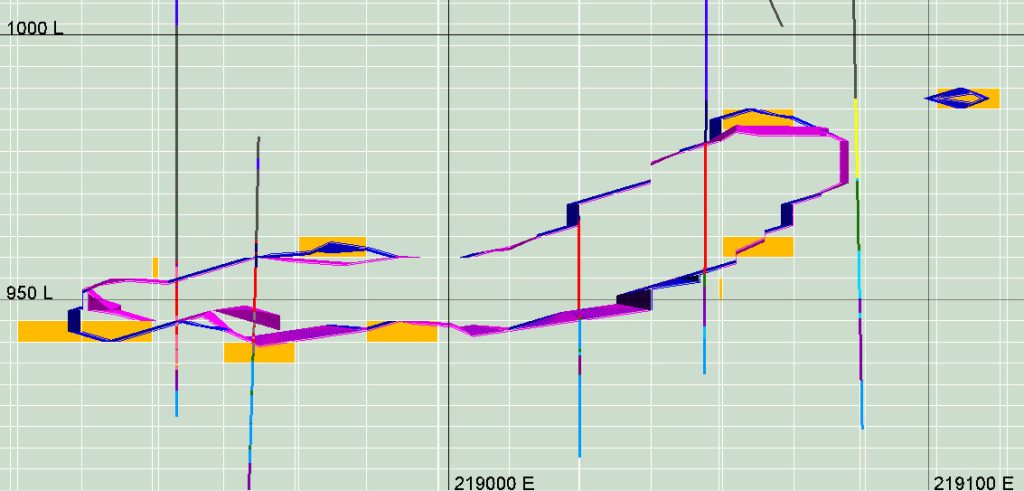

The two DomainMCF predictions from the top cross-section are shown against a background DomainMCF block model with spatial uncertainty in orange.

The domain uncertainty, based on three interpretations of this orebody, occurs largely on the contact margins between ore and waste.

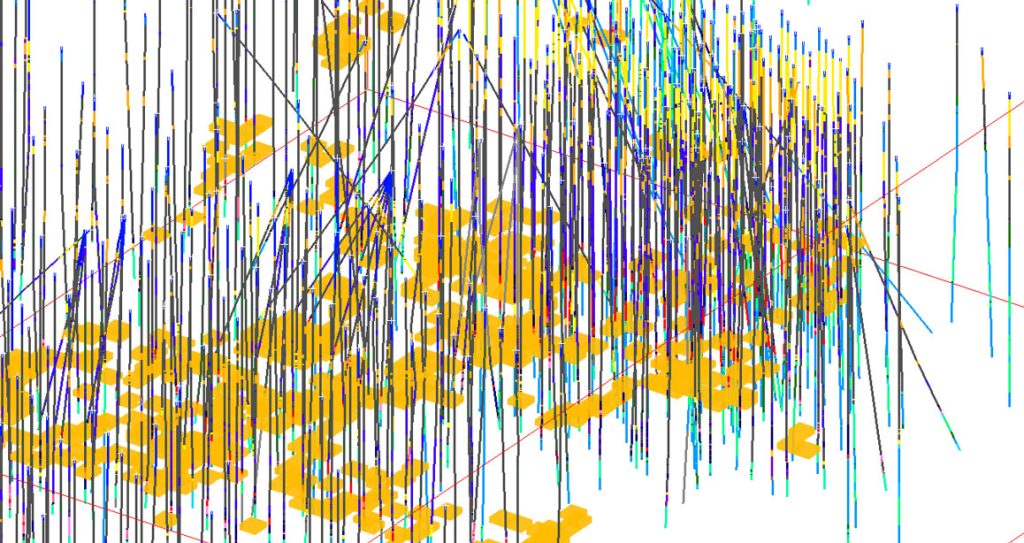

This 3D perspective view of the surface drilling for the Lisheen orebody provides clues to the challenges inherent in interpretation.

Even though the drilling appears closely spaced, the rapidly changing geological contacts in each hole provide a level of uncertainty as to the interpretations between adjacent drillholes.

In this deposit the majority of the geological uncertainty related to terminal margins of the mineralised horizon.